Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re reading “At the Mountains of Madness,” written in February-March 1931 and first published in the February, March, and April 1936 issues of Astounding. For this installment, we’ll cover Chapters 5-8 (roughly the equivalent of the April issue). You can read the story here, and Part I of our reread here. Spoilers ahead.

“It took only a few steps to bring us to a shapeless ruin worn level with the snow, while ten or fifteen rods farther on there was a huge roofless rampart still complete in its gigantic five-pointed outline and rising to an irregular height of ten or eleven feet. For this latter we headed; and when at last we were able actually to touch its weathered Cyclopean blocks, we felt that we had established an unprecedented and almost blasphemous link with forgotten aeons normally closed to our species.”

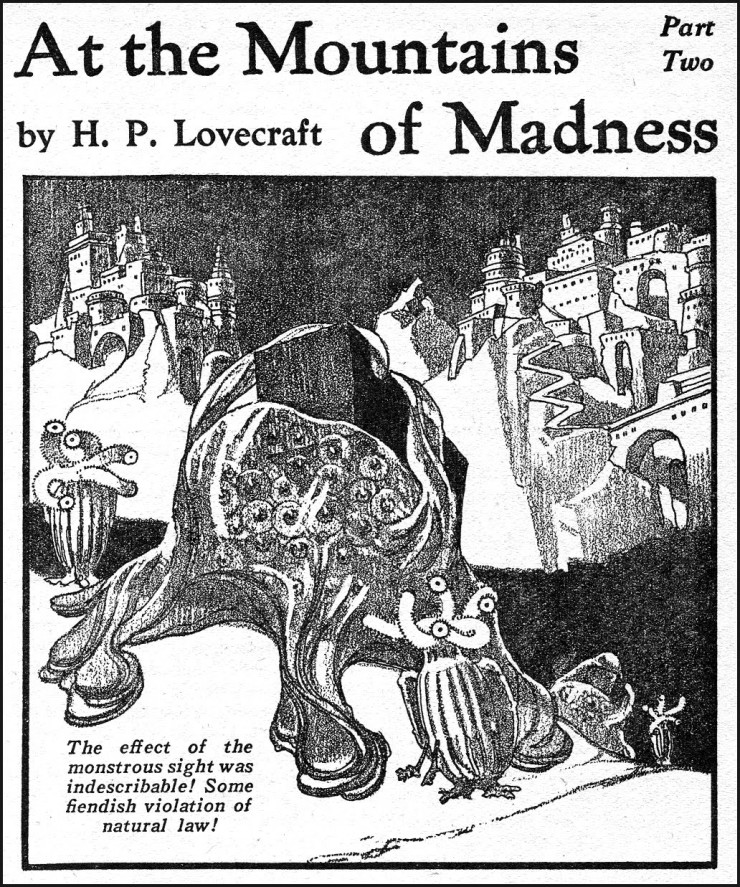

Summary: Dyer and Danforth finally top the mountains of madness and cry out in mixed awe, terror and disbelief. The mirage-city they saw en route to Lake’s camp had a material basis after all, and it now sprawls below them as far as they can see. From a layer of glacial ice rises a much-weathered but only semi-ruined metropolis which reason refuses to classify as a natural phenomenon. The incredibly varied buildings—cones, pyramids, cubes, cylinders, star-shaped edifices—can only be the ultimate expression of a civilization that reached its zenith when humans had yet to shamble out of apedom.

The pair make an aerial survey, determining the alien city extends thirty miles inland. Its span along the great barrier range seems endless. A building-free swath traverses the city, the bed of a broad river that debouches into whatever caverns honeycomb the mountains. Dyer doesn’t like the massive barrel-shaped sculptures that guard the river’s descent, and he finds this fabulous tableland too reminiscent of what he’s read of Leng, of Valusia, of Ib, of R’lyeh.

Danforth finds a snowfield in which to land the plane. He and Dyer venture into the aeons-deserted city, well-armed with compass, cameras, electric torches, notebooks, provisions and geologist’s tools. They examine the Cyclopean blocks and mortarless masonry, petrified wood shutters, any interiors into which they can crane. Through the gap left by a fallen bridge, they enter a largely intact structure. Interiors are decorated with carved murals in horizontal bands, edged by arabesque designs and inscribed with grouped dots. Now that they can study the murals close-up, they must accept that the primal race who carved them, who raised the city, were the same star-headed radiates Lake’s party found in fossilized form.

Fortunately for the explorers, the Old Ones (as Dyer names the radiates) were a historically-minded people who told their long, long tale in their murals. As the pair go from building to building, they piece together the outline of this tale. The Old Ones came to a still lifeless Earth from cosmic space, which they traversed on their membranous wings. At first they lived mostly beneath the sea, where they fashioned food and servants via well-known (to them) principles of biogenesis. Among these life forms were the amorphous shoggoths, which could take shape and do prodigious work in response to hypnotic suggestion. Eventually they built land cities and expanded outward from Antarctica. Other alien races arrived and warred with them. The Cthulhu spawn sank with their South Pacific lands, but the Mi-Go drove the Old Ones from their northern land outposts.

Other misfortunes overtook the Old Ones. They forgot the art of space travel, and the increasingly intelligent shoggoths rebelled against them and had to be put down. Terrible were the murals that showed the slime-coated, headless victims of the shoggoths. Later, when the Old Ones retreated from the growing glaciers, they bred new shoggoths capable of conversing in the Old One’s musical, piping language. But these shoggoths were kept in “admirable control” as they labored to construct a city in the sea at the roots of the mountains.

There’s something else the Old Ones feared. In some murals, they recoil from a carefully out-of-frame object washed down their river from certain mountains far inland, even taller than the mountains of madness. Mist hid this loftier range from Dyer and Danforth on their flight in.

Dyer supposes the Old Ones “commuted” between land and water cities until the cold grew too great. Then they fled permanently to the sea beneath the mountains, leaving the great metropolis to crumble. Of course, Lake’s specimens would have known nothing of this exodus. They lived in the land city’s “tropical” heyday thirty million years ago, while the “decadent” Old Ones deserted the land city 500,000 years ago. To be sure, Dyer had wondered about the eight undamaged specimens, and the grave, and the mayhem at Lake’s camp, and the missing provisions. Could Gedney really be the perpetrator of all this? And what about the incredible toughness and longevity of the Old Ones, portrayed in the murals? Then there were the excitable Danforth’s rather obnoxious mutterings about disturbances of snow and dust, and piping sounds he’s half-heard coming from deep in the earth.

Nah. Nah, it couldn’t be, and yet the specimens themselves and the alien metropolis could not have been, until they were. Even so….

What’s Cyclopean: The Old Ones’ city. A lot. Five times in this section alone, and 11 in the whole story, matching a record previously held by “Out of the Aeons.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Those slaves ought to have known their place, and been grateful to the masters who, after all, were responsible for their very existence… isn’t it just horrible that they didn’t agree?

Mythos Making: What doesn’t get called out? References to Leng and Kadath and Ib and the Nameless City, clashes between Old Ones and Mi-Go and Star-Spawn of Cthulhu, an origin story for R’lyeh. Then there are the shoggoths, who’ll continue to play boogey thing in hysterical rants for the remainder of the canon.

Libronomicon: It’s a good thing that this expedition was sponsored by Miskatonic University, where the Necronomicon and Pnakotic Manuscripts provide well-known frameworks for understanding alien monstrosity. Just imagine if our explorers came from a school whose Rare Books collection focused on a less practical topic…

Madness Takes Its Toll: Dyer worries he’ll be “confined” for reporting what he’s seen—while demonstrating xenophobia well beyond the pathological.

Anne’s Commentary

What is WRONG with the film industry, that it doesn’t want to capture in widescreen, CG’d, optional 3D’d glory that moment when our dauntless duo surmounts the peaks of madness and catches their first glimpse of the alien city beyond? Add epic score (by Howard Shore!), and the whole theater would gasp along with Dyer and Danforth. Not to mention the sheer joy of designing hyperrealistic Old Ones and shoggoths. Also albino penguins, for the Outer Gods’ sake! Don’t these people remember the success of March of the Penguins and Happy Feet? Of those penguins in the Madagascar movies? Of the blog FU Penguin?

If I were filthy rich, I’d be on the phone with Guillermo del Toro right now, poised to write a blank check. Because while there may be some things that should never be, there are others that cry out for realization, and a killer live-action Mountains is one of the latter.

Ahem. Valium taken.

One of the hardest things to translate to film would be the piecing together of the Old Ones’ history via their omnipresent murals. Put aside the outlandish technique of the art form, with its mind-boggling juxtaposition of the cross section with the two-dimensional silhouette—I mean, where are the great cubists when you need them to do your art design? This aspect of the novella would probably be condensed into key glimpses, like the explorers’ first clear look at a mural (OMG—the RADIATES built this city!) And, of course, loving slow pans of a decapitation by shoggoth and a recoiling from horrors unseen. Unseen, as in the story, because what could be worse than a shoggoth? Believe the Old Ones, you don’t want to know.

The Old One murals bring to mind the carvings in “The Nameless City,” which also amount to a condensed history lesson. A pictorial record is the obvious and sound choice where the “readers” don’t know the makers’ language. The significant difference between the “City” narrator and Dyer is that “City” struggles to the point of absurdity to deny that his discovery wasn’t built by humans. Even after he sees serpent people mummies, he tries to believe that they are merely totem animals, used as avatars by the human artists. Dyer is a true scientist. He admits that he can’t simultaneously believe that the transmontane spectacle is artificial, and that humans are the only intelligent species ever to walk the earth. Because, damn it Jim, he’s a GEOLOGIST, he knows how prehumanly old those rocks must be! Ergo, there were prehuman intelligences, and why not this amazingly complex radiate of Lake’s unearthing? Especially when it’s the star of all the murals.

And if you’re going to believe in Old Ones, what the hell, why not Mi-Go and Cthulhu spawn? Speaking of which, I wonder where the Yith are. The Old Ones don’t seem to picture them in their Australian stronghold, though their reigns on Earth must have overlapped. Nor do they picture the Flying Polyps. Hey, one monstrous nemesis per prehuman intelligence, please. I guess those weirdly bulging towers were just shoggoth reservoirs, one end of the Old One plumbing. Twist the sink knob with your nimble digital tentacles, and hey presto, out of the faucet pours however much shoggoth you need to perform a certain task. Done? Let the shoggoth ooze down the sink drain, back to its comfy tower bulge.

It strains credulity that Dyer could have determined much about Old One society and politics from brief inspection of the murals. Like, that they were probably socialists. Or that the “family” unit probably consisted of like-minded individuals rather than biological relatives. We have to remember that he’s writing long after the events, that he’s had time to study his photos and drawings and notes. He could be right, or his deductions could rely too much on his human perspective. I think he himself is aware of the danger. Infrequent reproduction via spores, personal longevity, comparatively slight vulnerability to environmental extremes, biological versus mechanical technology (including little reliance on vehicles due to superior self-mobility)—as we’ll read next week, the Old Ones may be “men,” but they’re far from men just like us. Yet, yet, the tantalizing commonalities of the intelligent life!

Through this installment, we pretty much forget about that Gedney guy our heroes were hunting for. You know, the one who might have freaked out, killed Lake’s party and dogs, carefully buried dead Old Ones, tinkered weirdly with camp machinery and provisions, then hiked off with a heavily laden sledge and only one dog. Yeah, seems less and less probable the more Dyer sees of the alien city. Even if he finds Danforth’s remarks about prints and pipings annoying, he can’t help thinking about the eight perfect specimens missing from Lake’s camp, and he’s not intellectually disposed to be as densely, willfully dubious as the narrator of “The Nameless City.”

Or, as Lovecraft rather elegantly closes Part Eight, Dyer and Danforth had been prepared by the last few hours “to believe and keep silent about many appalling and incredible secrets of primal Nature.”

Only Dyer won’t keep silent in the end, or we wouldn’t have another installment of “Mountains” to come!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Over the mountain rampart at last, and into the awesome, unlikely city of the Old Ones. While I still prefer the Yithian Archives (sorry, Anne), I’d happily spend far more than one day wandering among those bas reliefs, taking notes on symbolism and style…

Of course, I might be a little more cautious in my interpretations. Dyer seems awfully confident, not only that the murals accurately present millions of years of history, but that he’s correctly interpreted the visual narrative of an entirely inhuman culture. One wonders what he’d make of a Superman comic, or Shakespeare. How would he place the rise of Richard the First, chronologically, in relation to the political turmoil in Illyria, not to mention the reconciliation of Oberon and Titania?

As far as one can tell from their conveniently carved history, the Old Ones are the Mary Sues of the Mythos. They seeded life on Earth—accidentally, of course, no one would be so gauche as to claim deliberate responsibility for humanity. They fly through space like the Mi-Go (or could at one time). They build with scale and durability to rival the Yith (not mentioned by name here, probably not yet fully conceived). Their civilization lasted for longer than any other on Earth, covering both land and sea. Plus they bred through spores, like everyone Lovecraft approves of, and created families solely based on mental and social congeniality. (Howard, sweetie, it’s okay—humans are allowed to do that too. The household part, I mean, not the spores.)

And like everyone Lovecraft approves of, they are bigots of the highest order. The shoggoths are unproblematic when first created: basically remote-control masses of protoplasm. But when they start developing thoughts and speech and volition, do the Old Ones congratulate themselves on a successful uplift and offer them voting rights? How different from humans do you think these guys are? Naturally they wage a war of “re-subjugation.”

Dyer, of course, describes the Old Ones renewed control over the Shoggoths as “admirable.”

So, tell me if this sounds familiar. One set of people enslave another. They justify this based on both their own need, and an insistence that the enslaved people are better off under their control. And besides, on their own they’re savage brutes—just look what they do to us when we lose control, after all! And look what an elegant, civilized society we built with their aid. Such a shame it’s gone now…

The “lost cause” narrative of Old One history is scoring no points in this quarter, is what I’m trying to say. Go read Elizabeth Bear’s “Shoggoths in Bloom.” I’ll wait.

So clearly, I find the Old Ones horrifying and blasphemous for different reasons than Dyer and Danforth. I’m actually not entirely clear on the source of their distress—which stems not only from as-yet-unrevealed revelations, but from the mere existence of the city itself. Sure, “accidental byproduct of shoggoth construction” is nothing to put on your resume, but “first translator of artifacts from a non-human intelligence” sure is. And I have trouble buying that academics in the 30s were that different from the ones I know. When Dyer says, ‘Nevertheless our scientific and adventurous souls were not wholly dead,” and goes about “mechanically” exploring the find of a lifetime, I rather want to shake him.

You can totally tell that this is one of my favorites, right? It is, in fact—it just happens that I disagree violently with the opinions and reactions of every character. The intricate worldbuilding, and awesome alien art, make up for a cyclopean multitude of sins.

Last note—WTF Kadath? Apparently, the impossibly high mountains from Randolph Carter’s quest can be found deep in Antarctica. As can the plateau of Leng. Is the Antarctic boundary with the Dreamlands just extraordinarily porous? Has our narrator unwittingly crossed it? If so, that would explain the unlikely preservation of structures millions of years old, and the unlikely abilities of the people who once dwelt in those structures. Even if the next expedition goes on as planned, they may find Dyer’s research unexpectedly difficult to replicate.

Dyer and Danforth seek out the Old One’s hidden sea, and find more than they wanted to, next week in the finale to “At the Mountains of Madness.” Join us for Chapters 9-12, same eyeless albino bat time, same eyeless albino bat station.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in Spring 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the just-released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.